“When Cortés was at Coyoacan, he lodged in a palace with

whitewashed walls on which it was easy to write with charcoal and ink; and

every morning malicious remarks appeared, some in verse and some in prose, in

the manner of lampoons. . . . When Cortés would come out of his quarters of a

morning he would read these lampoons. Their style was elegant, the verses well

rhymed, and each couplet not only had a point but ended with a sharp reproof

that was not so naive as I may have suggested. As Cortés himself was something

of a poet, he prided himself on composing answers, which tended to praise his

own great deeds and belittle those of [others]. In fact, he too wrote some good

verses which were much to the point. But the couplets and sentences they

scrawled up became every day more scurrilous, until in the end Cortés wrote: 'A

blank wall is a fool's writing paper.' And next morning someone added: 'A wise

man's too.' . . . Knowing who was responsible for this, Cortés flew into a rage

and publicly proclaimed that they must write up no more libels or he would

punish the shameless villains.”

Bernal Díaz de Castillo,

True History of the Conquest of New Spain (1576)

True History of the Conquest of New Spain (1576)

There’s so much to say about Oaxaca’s local graphic arts scene and community, I feel like I’m trying to haul entire city blocks and over a century of local and national history in for a quick 5 minute show-and-tell. Impossible.

Iconography

ranging from traditional imagery (human and other animal figures, chickens

& skulls, the last supper, magueys & mescal, iguanas & maize

fields, colonial & revolution-era motifs & imagery, nahua pictography,

and of course, luchadores, Frida, Cantinflas, Zapata, Guadalupe, etc.) to more

contemporary and overtly activist work (names and faces of the missing, molotov

cocktails, hacking of multinational corporate brands, and blistering visual

commentary on political arrogance-corruption-repression, GMO’s, resource

privatization, trade policies, species extinction, gender injustice, etc.), all

unfolding through proper galleries; across guerilla collectives; and countless

studios/talleres, workshops, and

other public events and projects.

Let’s start with

the typical street-front art space. Approaching from outside, there’s already something

spilling out the doorway, splashed, brushed, stenciled, hand lettered, etc., extending

the full length of an outer wall. Inside, the first/main entry room or two is

hung salon style with current work, mostly prints—lino, woodcut, MDF/masonite,

silkscreens, stencils, etc. From there, a couple back or side rooms with

working studios, presses, shelves of equipment and materials, maybe a sleeping

cot, and people constantly making things.

Taller-Galeria Siqueiros, with their namesake revolutionary muralist rendered estilo hip-hop.

And Burro Press

is a brand new gallery/studio just opened earlier this month by Ivan Bautista, Edith Chavez, Alberto Cruz, et al.

In the city’s streets, one senses that the line between public and private space is being rewritten pretty constantly. Until 10 or so years ago, murals and other street art in the centro/downtown area was not prohibited. But a lot of this changed in the aftermath of 2006, making street art, like a lot of other public speech, more fugitive, ephemeral, fraught, and if I can say it without spitting elotes into your year and keyboard, a palimpsest. One that gets painted, seen, shotandposted, instagrammed, tweetedandretweeted, paintedoverandrepainted, and so on. A neighborhood exchange and global conversation by accretion in millimeters of paint and pixels. Or something anyway. Something more than slacktivism, more than just one carefully priced exhibition being replaced by another, or another billboard being routinely replaced by anotherbillboard, and so on. Also, higher stakes and with more skin in the game, I’d say.

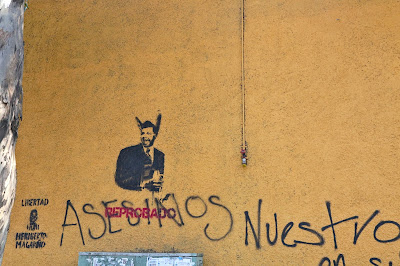

Ex: May 31, 2016

(Free César León, Peña Nieto: failure, etc.)

June 1, 2016

The new (PRI)

governor elect gets a quick public appraisal.

And much of this

from the Siquieros and Zapata art spaces—basically across the street from each

other on (ironically) Porfirio Diaz.

The last time I

went in, they were silk screening and watching a youtube where a guy goes out

at night and paints up the sides of 10-story buildings with a great big fire

extinguisher. No ladders, ropes or scaffolding. Just a guy in a hoodie working

from the sidewalk. I asked whether they knew how he’s able to get the paint—and

the tremendous pressure needed to reach all the way up the building—into the

extinguisher can. Simple, one kid explained to me, you just drill out the

pressure valve on top, fill the canister with paint, screw in a Schrader valve

(like in your bike tire), and pressurize the rest with an air compressor. Listo.

Also, a few more

articles worth checking out for background:

Jen Wilton’s2014 article for ROAR drops some good recent history, observing that, “After

all, graffiti that has been painted over simply becomes a blank canvas for

someone else to use.”

Kevin McCloskey offers 7 theories for why Oaxaca has become the center of Mexico’s visual art scene.

And here he gives

a fine historical overview and survey (as of 2012) of many of the studios and

collectives that have arisen in the last 10 years (since the state’s repression

of Oaxaca’s 2006 teachers strikes) including Shinzaburo Takeda’s great remark

that the city is “sinking like Venice under the weight of its printing

presses.” Also, some sound closing advise about brining a mailing tube on your

next visit to the city!

-->

related: Moose Curtis, hacking the city

No comments:

Post a Comment